We asked CANFAR National Ambassador, and Immunology Graduate Student at UofT – Rodney Rousseau, to give a crash course on HIV.

In this column, Rodney answers the question: “What does HIV do in the body?”

Overview

HIV invades and attacks white blood cells in your body. If your white blood cells were the size of a volley ball, a typical HIV particle would be smaller than a ping pong ball. Despite its size, HIV can do a great deal of damage to the human immune system.

A new HIV infection starts when someone is exposed to an HIV particle through the bloodstream (as can occur when sharing equipment for injection drug use), or through sites like the penis, anus, vagina, where sexual transmission most often occurs. Here’s a crash course on HIV:

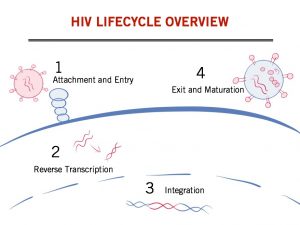

Regardless of how someone is exposed to HIV, a number of things happen as the virus establishes infection.

First Step

The virus interacts with white blood immune cells called “T cells”, which have a receptor molecule on them called CD4. This interaction is called “attachment”, and is the first step in producing more HIV.

Second Step

The second step is called “fusion”, and involves the virus releasing materials into the cell. This is followed by “reverse transcription” where these virus components produce viral DNA.

Third Step

That DNA will later be read by the cell in order to produce more HIV. But first, that DNA is “reverse transcribed” from RNA. It is used in the next step of the virus replication cycle called “integration”. During this step, the DNA is stitched into the human or “host” DNA. Once the virus DNA is stitched into the host DNA, the cell uses that DNA to produce more virus components. These components will “assemble” around the outside edge of the cell, and “bud off” as new immature virus particles.

Fourth Step

The final step of HIV replication is known as “maturation”, when internal virus components are processed to make it able to infect another CD4 T cell. Through this process, CD4 T cells are killed, and without access to anti-HIV medications, this ultimately leads to life-threatening disease and the progression to AIDS.

When someone is newly exposed to HIV, this process can happen very quickly, with many millions of virus particles spreading throughout the body. These viruses will infect CD4 T cells in different parts of body. In some cells, the virus is not instantly triggered to produce more virus, but instead lay dormant after the “integration” phase. This is known as virus “latency”, which is associated with “reservoirs” of HIV that persist in the intestine and lymph nodes. The very early establishment of latency and reservoirs is part of the reason why an HIV cure has been so elusive to-date. Treatments that target the steps of HIV replication have done much to improve life expectancy and quality of life for those of us living with HIV, but ultimately, we require continued impactful research that is targeted at the biomedical barriers holding us back from an HIV cure.

Authored by Rodney Rousseau